During lactation, there is increase in protein levels that regulate eating behavior, sleep and stress, and early weaning may cause imbalances

Much is already known about the benefits of breastfeeding for the offspring’s health. What is little discussed – perhaps due to the small number of pieces of research that addresses the subject – is how much females’ brains change when their babies begin the weaning process, and the repercussion of early weaning on their behavior.

A recent contribution to this understanding came from a doctoral thesis conducted with mice at USP’s Institute of Biomedical Sciences (ICB). Researchers have found that levels of orexin, neuromodulator connected to eating behavior, sleep and stress, increased during lactation. According as weaning process progressed, levels decreased up to normality at the end of the period.

In mice, the teeth begin to erupt on the 14th day of life. Weaning process begins on the 15th day – the babies already walk, see, hear and feed on solids – and ends on the 22nd day, when the offspring stop interacting with the mother.

When the researchers promoted early weaning and prevented the babies from keeping on breastfeeding, the females were, on the 22nd day, with the same levels of orexin they had on the 15th day. “Higher levels of orexin in the brain may lead to sleep disorders, such as insomnia, increased stress, and even depression, as response to this higher stress,” neuroscientist Giovanne Baroni Diniz, author of the study, affirmed. He explains that in narcolepsy (excessive drowsiness), the levels of this neuromodulator are very low.

The study was conducted at ICB’s Department of Anatomy, under Professor Jackson Cioni Bittencourt’s guidance. The findings were considered so relevant that the neuroscientist received an invitation to defend the thesis at Maastricht University, in the Netherlands, last December, under Professor Harry W. M. Steinbusch’s supervision, and obtained double degree doctorate.

“In functional terms, the study brings new data by demonstrating the role of orexin in lactation and weaning, leading to neuronal alterations of great magnitude in the maternal brain,” the neuroscientist explained.

Increase of this neuromodulator during breastfeeding is justified because the female needs to be more attentive to protect the offspring, and the orexin promotes exactly that. In turn, in a virgin female, the number of neurons attached to the neuromodulator is similar to that of mice with babies at the end of weaning.

Experiments

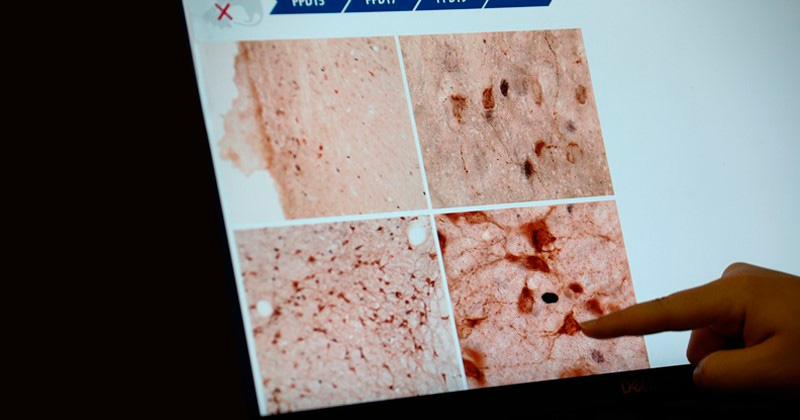

In the laboratory, the scientists promoted the early weaning of babies at 15, 17, 19 and 21 days of life. Soon after, they analyzed their mothers’ brains, specifically the hypothalamus region, which is very important to lactation, and where the neurons connected to the orexin are found. They used the FOS protein as a marker, since it indicates to scientists that the neuron was active an hour or two before analysis. Thus, the researchers can be sure of which neuron was activated at the time of weaning.

When analyzing the animals’ brains, they observed high levels of orexin activated, in amount higher than that found in the control group (virgin female mice). The researcher emphasizes that, in the hypothalamus, orexin splits locally into two groups: on the lateral side, there are the neurons that act on eating and rewarding behavior; and in the medial region (in the center) are those neurons associated with attention (stress) and sleep. In the experiment, they realized that practically the majority of active orexin cells were in the medial region.

The video below shows the 3D reconstruction of the hypothalamus. In yellow, the orexin cells activated hours earlier in the medial region are highlighted.

The results of the study point to the need for doctors to pay close attention to mothers who stopped breastfeeding. “The doctor should be aware of alterations in the pattern of sleep, or emotional changes that persist for a long time, because this mother may not have returned to normality,” he explained.

Giovanne Diniz explained that there is much that is not known about the nervous system and the process of lactation and gestation. “It’s an area that has a lot of room for research development. Historically, in science, there was a tendency not to use female subjects. Many studies only look into males. Therefore, in terms of women’s health and understanding the women’s physiological mechanisms, people know less,” he affirmed.

MCH: Melanin concentrating hormone

At the beginning of the doctoral research, the neuroscientist Giovanne Diniz started from the analysis of scientific articles showing brain alterations during gestation and lactation. About 20 substances have been detected. Among them, he has found the melanin concentrating hormone (MCH). In humans, it acts as a neuromodulator, that is, it is produced by neurons to alter the functioning of other neurons.

Scientists hypothesized that MCH could be associated with lactation because a group of these neurons appears in the female mice’s hypothalamus at the end of lactation. The same does not occur in males, in pregnant rats, at the beginning of the period, or even after, when the babies are weaned. However, after several experiments, researchers have discovered that it is orexin – not MCH – that performs a more specific role in lactation and weaning.

Double degree

The thesis to be defended at ICB addresses MCH performance in the body, and specifically with regard to how it communicates with the other nervous system cells. Orexin, in turn, was the subject of the thesis defended at Maastricht University.

Giovanne Diniz said that the prerequisites to defend the thesis in the Netherlands were: to be the first author of three papers on such research, and Netherlands’ thesis papers not allowed to participate in USP’s study.

The neuroscientist wrote the thesis, sent it to a Maastricht’s evaluation committee, and the work was accepted.

And without having to take any course at the Dutch university, Giovanne Diniz received his doctoral degree from Maastricht University. As for the defense at ICB, it is expected to occur until the second half of this year. After that, Diniz will have double-degree doctorate: one from the Dutch university, and other from USP.

Valéria Dias – Jornal da USP